Most people speed past it along the A422 Banbury to Stratford road. Even if they notice the monument, they may not realise what it is. But look deeper into the meaning of this insignificant stone pillar, and it can tell you a centuries old story about the local landscape, and the changing state of the nation.

The story of the ‘Wroxton Fingerpost’ shows how the world around this ancient stone has been reshaped by political and economic forces, as great as anything happening today; ones which are still at work, in the stone quarrying all around this location, and the intensive industrial monoculture of the surrounding fields.

© 2022 Paul Mobbs; released under the Creative Commons license.

© 2022 Paul Mobbs; released under the Creative Commons license.

Created: 5th February 2022;

Updated: 13th March 2022.

Length: ~1,500 words.

Location: Wroxton, Oxfordshire

Type: ‘Standing Stones & Circles’.

Condition: At least 250-year-old guidepost, restored in the 1970s.

Access: Beside the A422 Banbury to Stratford road.

OS Grid Ref.: SP408416

Further information: Long Walks and Anarcho-Primitivism Blog.

Walks posts or videos for this site:

The stone is square, with an inscription on one side, and on the other three sides, carved fingers which point the way to their respective destinations:

On face without a finger, on the village side, the inscription reads, “First given by Mr. Francis White in the year 1686”.

White had been a steward to the powerful North family – the Barons of Guilford – who bought the nearby Wroxton Abbey in 1677. Little is know of White, except that he gave this monument to the village.

It says “First given”, because there is some dispute as to how authentic this stone is. It may be the remains of the one erected in 1686. It may have been replaced when the North family created their landscaped park almost a century later. What we do know is that in the 1970s, the stone was completely reworked to hide two centuries of graffiti – removing over a centimetre of stone off of each face, and re-carving the fingers and inscriptions.

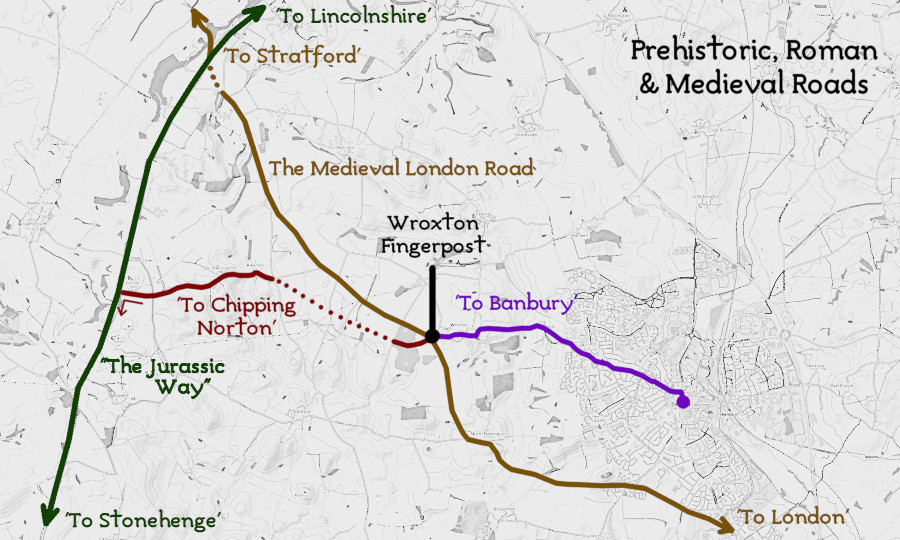

On the south-east face, the finger points, ‘To Banbury’. Cast your eye across to the road, and the modern sign and it points there too. On the the south-west face, one finger points left, ‘To Stratford’, where the modern sign points too. But above it the finger above it points right, down a single-track road, ‘To London’. How can that be? The main road leads to Banbury, but this little road winds down narrow lanes to nowhere.

Finally, on the north-west side, the finger points, ‘To Chipping Norton’ – across the nearby fields. Not only is there no road there, but that’s not even the way towards Chipping Norton!

What this stone is tells you is the five-thousand-year history of how people have moved across this landscape. To understand that, we need to look at a map of the local area.

The Medieval road from Stratford to London did not pass through Banbury. It didn’t even follow the A422. North-west from here, near Upton House, it swung north, down the escarpment along King John’s Lane, and on past Edgehill’s Civil War battlefield to Kineton. Over centuries of use it’s path shifted as erosion required its course to be re-cut on the steep hillside. Those changing routes are still visible as depressions in the wooded ground surface today.

In the London direction, along the narrow lane, the road joined the Roman ‘Salt Way’ near the village of North Newington. This ran from Droitwich, crossing the river at Stratford, then taking a straight line to Broughton and Bodicote, where it crossed the River Cherwell. From there it went to Buckingham, connecting with the road to London along Roman ‘Watling Street’.

The finger pointing into the field towards Chipping Norton is follows an even more ancient route. Three hundred years ago, the quickest way to Chipping Norton would have been to follow that path, through the villages of Balscote and Shenington, and then turn left down ‘The Jurassic Way’ – where the paths met, auspiciously (?) at the local highest hilltop, Shenlow Hill. That trackway leads directly to Chipping Norton, going on after that to Burford, Avebury, and Stonehenge.

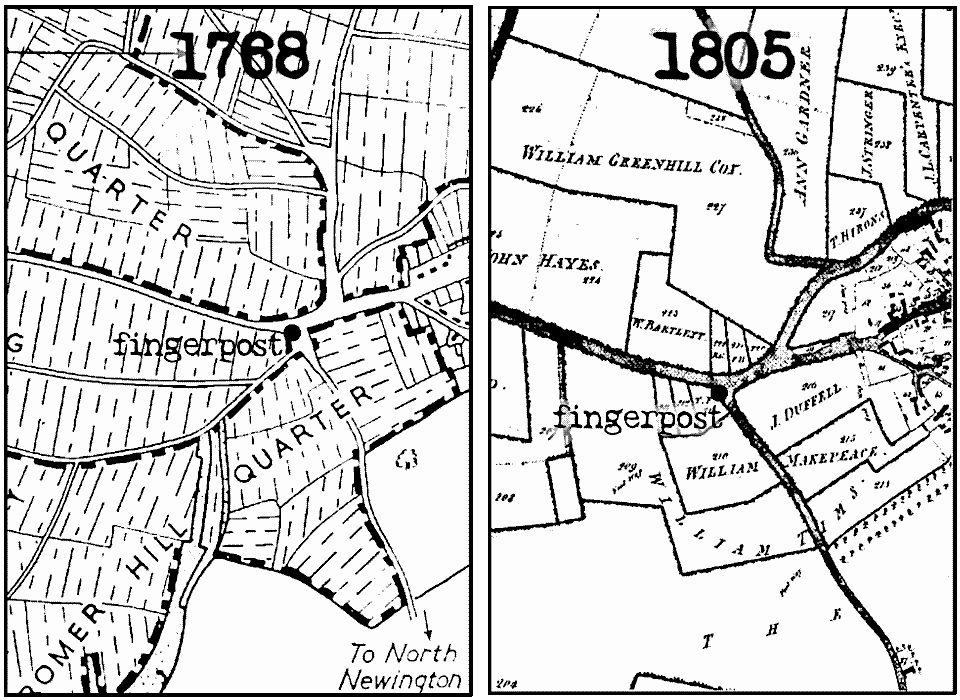

If we look at this map of Wroxton in 1768 (below), you can see that there are many roads west from the village which link to an extensive open field system. This field system had been established in the Thirteenth Century by the Augustinian priory. That lasted until it was ‘privatised’ by Henry VIII, and parcelled out to his friends in the Sixteenth Century. Locally that was the Pope family, who in turn gave the land to found Oxford’s Trinity College; and sold the remains of the priory to the Barons of Guildford, to be their country estate.

During inclosure, which took place around 1800, these open fields, along with the common land which local people subsisted on, were enclosed with hedges – creating the landscape we see today. Locally, with their livelihood taken away, the inclosure of the local parishes swelled the ranks of the landless poor. This led to the Swing Riots of the 1830s, and to the establishment of the new, larger Union Workhouse on the road into Banbury – which, more than anything else, created the boundaries of what today the local tourist lobby call, ‘Banburyshire’.

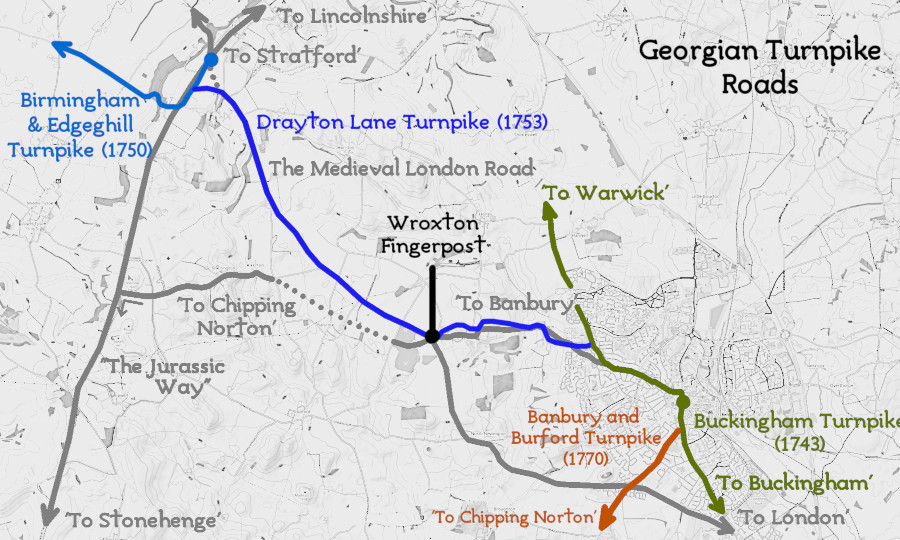

Along with that inclosure of the land, around the same time we see the creation of the first national road system since the Roman era – the turnpike roads. These roads were better than the Medieval roads. They had a compacted stone surface to support the cart and carriage wheels. The big difference was that the turnpike trusts, created by Parliament to maintain them, charged a fee for their use. In effect, Parliament created private corporate monopolies, and people had to pay the price.

The first turnpike road to Banbury from London arrived in 1743. It followed the route of Roman Watling Street to Buckingham, and then along the Roman Salt road to Banbury. From there it followed the Medieval ridge route towards Warwick.

Due to the way Parliament and local government operated, turnpikes ran to and from the county border. Birmingham was then in Warwickshire. For this reason, in 1750, the Birmingham turnpike ran to the Warwickshire border, at Edgehill, but could go no further. Rather than use the Medieval route, as often was the case with the new turnpikes, they cut an engineered track up the escarpment at Sunrising Hill – which forms the route of the modern road today.

Finally, in 1753, the Drayton Lane turnpike connected these routes together, running past the ‘Wroxton Fingerpost’. Then finally, making the ancient ‘Jurassic Way’ obsolete, the Banbury, Chipping Norton and Burford turnpike opened in 1770.

Today’s modern road network – created in its current form between 1919 and 1936 – still echoes those ancient routes: The A422 into Banbury roughly follows that Medieval road, going through Buckingham to join Roman Watling Street, the modern A5, near Milton Keynes; the A41 still follows the mainly Roman roads towards London, though these days it’s importance has been demoted by the arrival of the M40; and, the A361, running to Chipping Norton, follows the route of that prehistoric road from the Leicestershire border down to Avebury.

The Wroxton Fingerpost is, on the face of it, a throwback to an earlier time, and the national influence of a local aristocratic family. Look deeper though, especially if you have wandered the footpaths and roads on the way here, and the centuries of change that this stone has witnessed has a meaning equally relevant to the world as it is today.