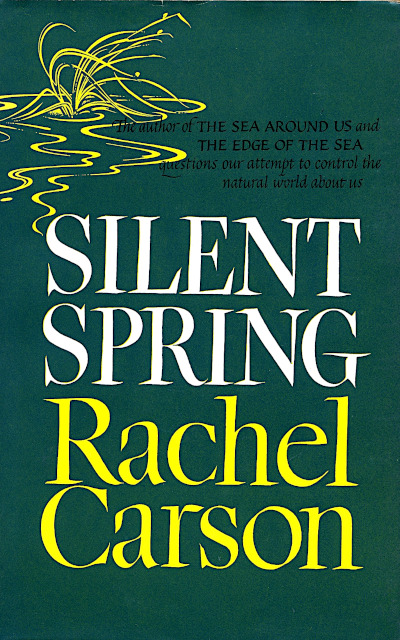

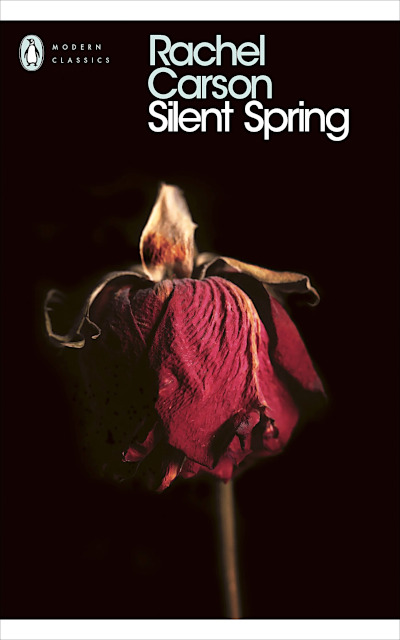

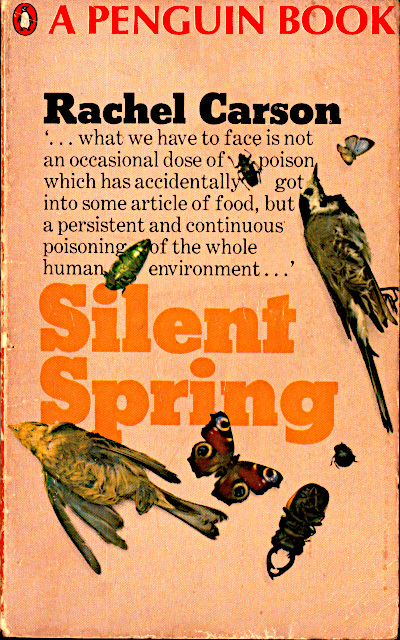

‘Silent Spring’,

Rachel Carson (1962)

An historically significant book, its hypothesis proven right, its message undimmed by the passing of six decades – and yet it is so seldomly discussed today.

© 2022 Paul Mobbs; released under the Creative Commons license.

© 2022 Paul Mobbs; released under the Creative Commons license.

Created: Monday 23rd May 2022;

Updated: Tuesday 24th May 2022.

Length: ~1,000 words.

Click for hotkeys list (or press hotkey-K).

‘A Book in Five Minutes’ No.13 Podcast:

Download podcast as an MP3 or an Ogg Vorbis file.

Click for keyboard instructions (or press hotkey ‘X’)

‘Silent Spring’:

First Edition, Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

Penguin Modern Classics (mass-market paperback, multiple reprints over last 20 years).

Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Houghton Mifflin, 2002. ISBN 9780-6182-4906-0.

The value of living in the same place all your life is that it get an innate sense of change. And after fifty years of being in this area, I sense just how much the landscape has changed. Forty years ago I read a book which not only explained that to me, but primed me to see that whole process unravelling.

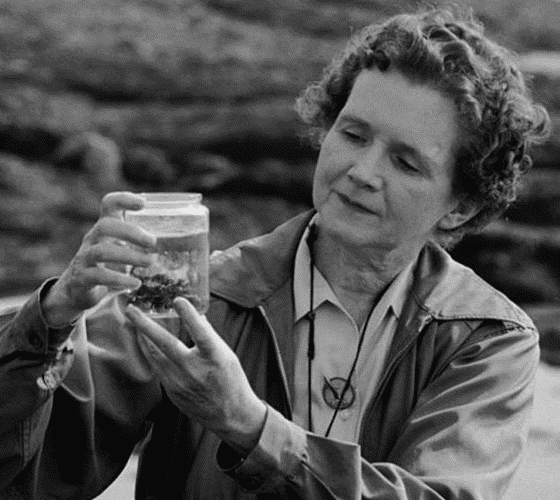

‘Silent Spring’, by Rachel Carson, was published sixty years ago. This book can be said to have crystallised Western consciousness on humans and the environment (though we must admit that indigenous writers had said this long before, but Western reductive science was blind to its meaning).

The book’s title comes from a realisation – being enacted today with the death of insect populations, the loss of songbirds, and the collapse of ecosystems:

“Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song. This sudden silencing of the song of birds, this obliteration of the colour and beauty and interest they lend to our world have come about swiftly, insidiously, and unnoticed by those whose communities are as yet unaffected.”

Today we are awash with news on the impacts of chemical pollution: Of ‘persistent organic compounds’ that are building-up in the environment; exceeding toxic levels; and polluting all aspects of our lives.

Carson foresaw these events sixty years ago.

At the time, the responses to Carson from “the men in white coats”, though made from a position of technocratic authority, were infused with misogyny. And in what became be the first systematic use of the ‘tobacco industry playbook’, the chemicals lobby sought to destroy her reputation, and the message of the book.

Carson’s position is clearly stated:

“In the less than two decades of their use, the synthetic pesticides have been so thoroughly distributed throughout the animate and inanimate world that they occur virtually everywhere. They have been recovered from most of the major river systems… Residues of these chemicals linger in soil to which they may have been applied a dozen years before. They have entered and lodged in the bodies of fish, birds, reptiles, and domestic and wild animals… and man himself.”

The observations and predictions the book makes have stood the test of time. Its deeper analysis of the natural environment and technocracy – and in particular the illusion of “man’s control” over the environment – still hold true despite six decades of technological and regulatory change.

The points Carson makes with regard to the industry’s obfuscation of oversight, and the vacillating role of public regulators, persist to this day:

“The crusade to create a chemically sterile, insect-free world seems to have engendered a fanatic zeal… It is not my contention that chemical insecticides must never be used. I do contend that we have put poisonous and biologically potent chemicals indiscriminately into the hands of persons: largely or wholly ignorant of their potentials for harm… It is also an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged. When the public protests… it is fed little tranquillizing pills of half truth.”

Where the book excels, though – in a manner that would not become widespread until James Lovelock’s ‘Gaia Theory’ – was advancing the idea that we are part of the natural environment, not separate from it; and therefore, as in the epithet that embodied the first wave of radical environmentalism, “what we do to the Earth we do to ourselves”:

“The history of life on earth has been a history of interaction – between living things and their surroundings… Only within the moment of time represented by the present century has one species – man – acquired significant power to alter the nature of his world… This pollution is for the most part irrecoverable; the chain of evil it initiates not only in the world that must support life but in living tissues is for the most part irreversible.”

The willing ignorance of the chemical industry shows it to be based not upon ‘science’, but upon an economic ideology. And while climate change might grab most of the headlines, the fact is that chemical contamination is equally pressing.

Reading this book today it appears new; it speaks to contemporary issues. Therefore we have to ask why, decades after it was written, there is still no global agreement to eliminate these substances:

“…we are dealing with life – with living populations… The current vogue for poisons has failed utterly to take into account these most fundamental considerations. As crude a weapon as the cave man’s club, the chemical barrage has been hurled against the fabric of life… These extraordinary capacities of life have been ignored by the practitioners of chemical control who have brought to their task no ‘high-minded orientation’, no humility before the vast forces with which they tamper.”

As I write: The COP15 conference on biodiversity is still shelved, despite a catastrophic acceleration in biodiversity loss; and new revelations about the extent of chemical contamination emerge continually. And yet, through all this, little credit is given to the person who foresaw these trends, and why her analysis is still valuable six decades later.

In my view, not enough ‘environmentalists’ are reading ‘Silent Spring’. It was a book before its time. For this reason, and for its timeless prose as well as the science it relates, it’s still required reading today.