© 2022 Paul Mobbs; released under the Creative Commons license.

© 2022 Paul Mobbs; released under the Creative Commons license.

Created: 29th October 2022.

Length: ~1,600 words

Click for hotkeys list (hotkey ‘K’)

Download podcast as an MP3 or an Ogg Vorbis file.

Click for keyboard instructions (or press hotkey ‘X’)

As British people currently wrestle with the reality that they do not have the power to choose the governing executive of their nation – and that their representation is in actuality in name only, and renders little political control – it’s fitting that we celebrate the 375th anniversary of one of the significant events of English history… and the 374th anniversary of Thomas Rainsborough’s death.

Across political history, The Putney Debates are significant because they represent one of the first instances where representatives of ordinary people discussed the fundamental nature of the state which governed them. As with many other such significant events in our history, these debates, as you would expect given the patrician nature of the British state, are rarely discussed; but the substance of those discussions still dominates the political situation in Britain today.

The debates took place over two weeks in St. Mary’s Church in Putney, from Monday 28th October to Friday 8th November 1647 (there is a permanent exhibition in the church). The point about being in a church wasn’t simply that it was a space for a meeting. In the character of debates at this time, those involved would spend time in silent reflection and prayer while they considered what was being said (an ancient form of spiritual discernment, still preserved today in the conduct of Quaker meetings).

The ideas at the heart of that debate were presented in the Leveller manifesto, ‘The Agreement of the People’. The Grandees, representing the landed gentry who held power in Parliament, didn’t like what was proposed one bit – precisely because it would open-up the conduct of government to a representative body of all people; not just the aristocracy and the landed elite who had stacked the Parliament until that point.

This is why the political backdrop to The Putney Debates has resonance today: Right now, with rising inequality and the collapse of the post-war economic consensus, we are facing – in a very real sense – the emergence of a form of technologically-enabled ‘neofeudalism’. An asset-rich minority increasingly extract wealth from the vast majority of the population, and that ‘landless’ population has very little direct control or voice in the terms of that economic arrangement. This was the case 375 years ago; and one of the motivations of the English Civil War was the promise that this situation might be reformed in the aftermath of the conflict.

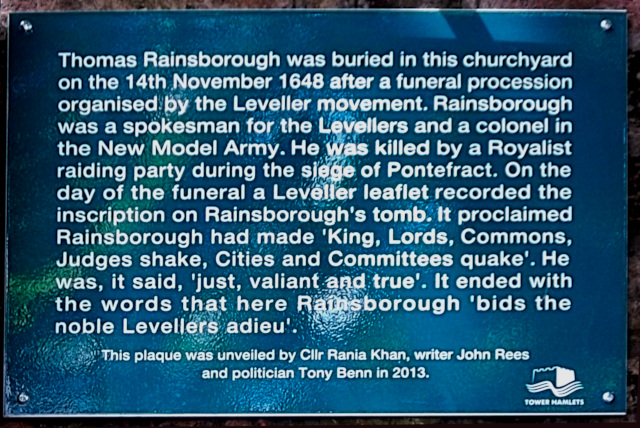

It didn’t happen: Eighteen months after the debates the core of the group calling for this change – The Levellers – would be broken-up by Cromwell. Their ideas would be suppressed, not resurfacing until the rise of political radicalism and The Chartists two centuries later.

There was no contemporary record of The Putney Debates. A transcript was made by the Secretary to the Army, William Clarke, which largely covered the discussions on 29th October after the presentation of ‘The Agreement of the People’. It was not published at the time, and was lost until 1890, when the transcription was discovered in the library of Worcester College, Oxford.

The text of The Putney Debates is available in book form, or an PDF on-line. It is a debate between about a dozen men at the heart of Cromwell’s New Model Army. It’s very long, and there seems little point in reproducing it here – if only because in the modern context it requires a deeper analysis to understand the perspectives involved.

I first read the ‘modern’ text (re-written in modern English from the shorthand notes transcribed by William Clarke) when it was published in 1998. At that time, what found I the most compelling were the contributions from Thomas Rainsborough – one of the leading Levellers, and one of the main contributors to the debate who spoke in in opposition to the Army grandee, Henry Ireton.

What follows, then, is an edited form of Thomas Rainsborough’s speeches during The Putney Debates; edited to give a sense to the political consciousness of The Levellers at that time, so that we may contrast what progress has been made over the last 375 years. At that time, what Rainsborough said was ‘revolutionary’. The notion of taking political power from our modern economic elite is, today, equally revolutionary:

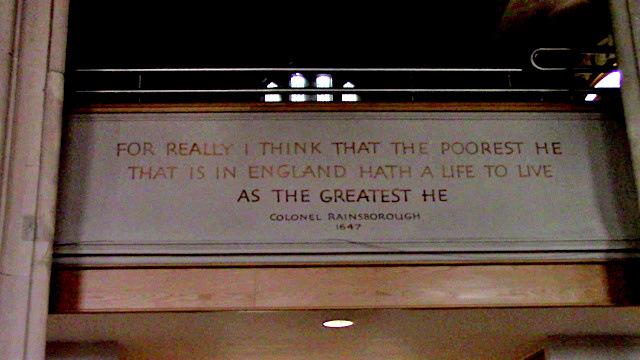

I think that the poorest he that is in England has a life to live as the greatest he; and therefore truly, sir, I think it's clear that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that government that he has not had a voice to put himself under.

I do hear nothing at all that can convince me why any man that is born in England ought not to have his voice in the election of burgesses {Medieval equivalent of local councillors and members of Parliament}. It is said that if a man have not a ‘permanent interest’ he can have no claim; and that we must be no freer than the laws will let us be; and that there is no law in any chronicle will let us be freer than that we now enjoy.

Truly I think that there is not this day reigning in England a greater fruit or effect of tyranny than this very thing would produce. Truly I think that the people of England have little freedom. I am a poor man, therefore I must be oppressed? If I have no interest in the kingdom, I must suffer by all their laws – be they right or wrong?

To the thing itself – property in the franchise. I would know how it comes to be the property of some men and not of others. If it be a property, it is a property by a law; because I think that the law of the land in that thing is the most tyrannical law under heaven. This is the old law of England, and that which enslaves the people of England: that they should be bound by laws in which they have no voice at all!

I desire to know how this comes to be a property in some men and not in others; how it comes about that there is such a propriety in some freeborn Englishmen, and not in others. What has the soldier fought for all this while? He has fought to enslave himself, to give power to men of riches, men of estates, to make him a perpetual slave?

If these men must be advanced, and other men set under foot, I am not satisfied. If their rules must be observed, and other men that are not in authority be silenced, I do not know how this can stand together with the idea of a free debate. I wonder how that should be thought wilfulness in one man that is reason in another. And therefore, till I see that, I shall use all the means I can, and I think it is no fault in any man to refuse to sell that which is his birthright.

End of the page. jump to the top of the page